Mass Points and Barycentric Coordinates Basics

Mass Points as a Physics Problem

Given some center of mass on a segment, mass points allows you to assign relative masses to two other points given their lengths from the center. The conclusion comes to, if your center \(C\) is a distance \(r_A\) from point \(A\) and \(r_B\) from \(B\), you can assign masses \(k * r_B\) to \(A\) and \(k * r_A\) to \(B\), where \(k\) is some constant, to balance their masses at \(C\). Then (for mass points reasons) you can assign mass \(k *(r_A + r_B)\) to \(C\).

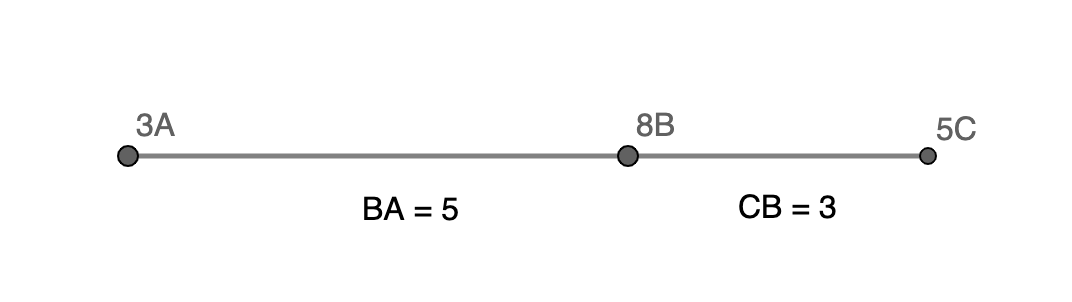

(sorry for the differently labeled diagram) In the example, \(A\) has mass \(3\) and \(C\) has mass \(5\) because \(\frac{AB}{BC} = \frac{5}{3}\).

(sorry for the differently labeled diagram) In the example, \(A\) has mass \(3\) and \(C\) has mass \(5\) because \(\frac{AB}{BC} = \frac{5}{3}\).

If we call the mass and distance to center \(C\) of \(A\), \(m_A\) and \(r_A\), respectively and for \(B\), \(m_B\) an \(r_B\), we can see that \(m_Ar_A = m_Br_B\). It kind of looks like a physics problem! If you’ve ever seen the torque problem of two people balancing on a seesaw or something of the sort, you’ll recognize that if you were to place segment \(AB\) (referring to the earlier \(AB\), I will change the diagram) on a fulcrum at \(C\), with those given masses, it will balance.

Quick summary of torque. It’s rotational force, as in, something measuring the strength of a change in the rate of rotation. Its equation is given by \(\tau = rF\sin\theta\), where \(r\) is your distance from the point of pivot (it makes sense that it would be greater for larger radius), \(F\) is your directly applied force, and \(\theta\) is the angle that your pivot point makes with the applied force. In this situation, with gravity, the two points \(A, B\) will exert downward force perpendicular to the pivot point, and we want their torques to be of equal magnitude (and opposite direction). So, we can set \(\tau_A = \tau_B\) or \(r_AF_A\sin\theta_A = r_BF_B\sin\theta_B\), if we only consider the magnitude of each \(F\). \(\theta_A = \theta_B = 90^\circ\), so sine expressions cancel, and so will gravitational constants for \(F_A\) and \(F_B\), so we are left with \(r_Am_A = r_Bm_B\). And the force on the segment acts directly on \(C\), so \(C\) experiences the force of mass \(m_A + m_B\) (which explains the mass given to \(C\)).

Mass Points as a non-Physics Problem

In triangles, we can do something similar in order to get points to balance. If we are length chasing and we are given some ratio of lengths along some segment, we can assign arbitrary masses in proportion that will evaluate other length ratios.

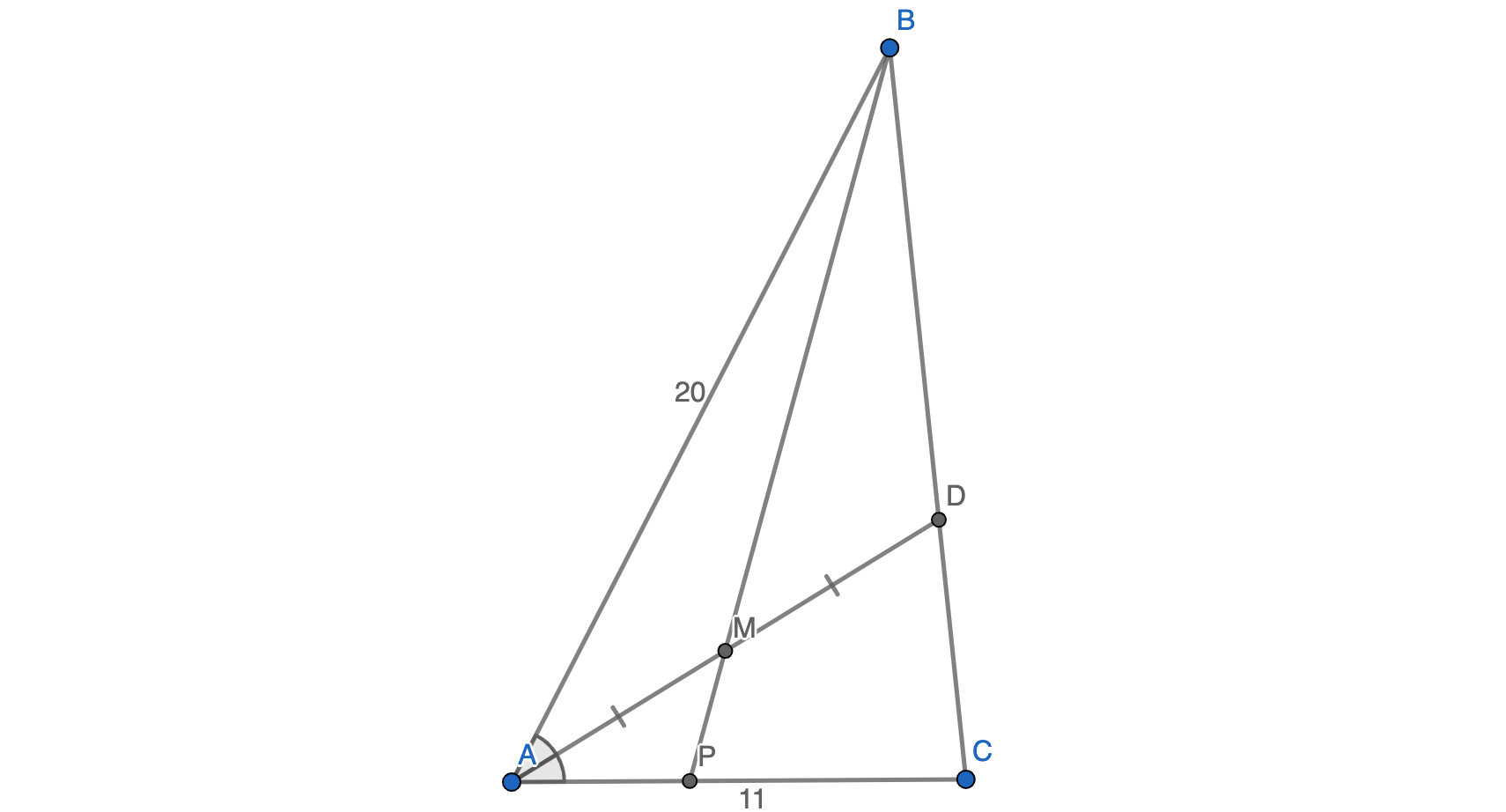

Here’s an example (2011 AIME II Problem 4):

Problem: In triangle \(ABC\), \(AB=20\) and \(AC=11\). The angle bisector of \(\angle A\) intersects \(BC\) at point \(D\), and point \(M\) is the midpoint of \(AD\). Let \(P\) be the point of the intersection of \(AC\) and \(BM\). Find the ratio of \(CP\) to \(PA\).

Solution:

\(m(X)\) will denote the mass assigned to point \(X\).

By angle bisector theorem, \(\frac{BD}{DC} = \frac{AB}{AC} = \frac{20}{11}\). So, let’s assign mass \(20\) to \(C\) and \(11\) to \(B\), therefore mass \(31\) to \(D\). \(AM = MD\) so \(m(A) = m(D) = 31\). Therefore \(\frac{CP}{PA} = \frac{m(A)}{m(C)} = \fbox{ 31/20 }\).

Exercises

- In \(\triangle ABC\), points \(D\) and \(E\) lie on sides \(BC\) and \(BA\) respectively, \(\frac{BD}{DC}=\frac{5}{2}\), and \(\frac{BE}{EA}=\frac{3}{4}\). Let \(F\) be the intersection of segments \(AD\) and \(CE\). Find \(\frac{EF}{FC}\) and \(\frac{DF}{FA}\).

- Use mass points to prove that the medians of a triangle are concurrent and divide each other in a ratio \(2 : 1\).

- In \(\triangle ABC\), \(E\) lies on \(AB\), \(D\) lies on \(BC\), \(G\) lies on \(AC\), and \(F=ED \cap BG\). Furthermore, \(\frac{AE}{EB}=\frac{4}{3}\), \(\frac{BD}{DC}=\frac{5}{2}\), and \(\frac{AG}{GC}=\frac{3}{7}\). Find \(\frac{EF}{FD}\) and \(\frac{BF}{FG}\).

Barycentric Coordinates

This draws from an idea similar to mass points.

Definitions:

- Relative to a triangle \(\triangle ABC\), a point \(P\) is given (non-absolute) barycentric coordinates \((a : b : c)\) if points \(A, B, C\) are assigned masses \(k*a, k*b, k*c\) respectively in order for \(P\) to be the triangle’s center of mass (\(\star\)).

- This is equivalent to the following (more precise) vector definition: point \(P\) can be assigned a unique triple of reals \((a, b, c)\) such that \(\overrightarrow{P} = a\overrightarrow{A} + b\overrightarrow{B} + c\overrightarrow{C}\) and \(a + b + c = 1\).

- Absolute barycentric coordinates \([a : b : c]\) are scaled such that \(a+b+c=1\).

- Signed areas in the case of barycentric coordinates are positive when within the interior of the triangle, and negative outside.

Theorem: if \(P\) has barycentric coordinates \((a : b : c)\) relative to \(\triangle ABC\), then these coordiates are equivalent to the signed area ratio \(([PBC] : [PCA] : [PAB])\).

Proof: This will rely on the vector definition, and because I do not want to vector bash, some sort of affine mapping that will preserve area ratios and map \(\triangle ABC\) to a certain triangle placed at rectangular coordinates \(A = (0, 0), B = (1, 0), C =(0, 1)\). Note that any triangle can be mapped to any other triangle via some affine transformation.

Now, \(P\) can still be any point \((x, y)\), in which case we see that coordinates \((1-x-y : x : y)\) indeed satisfy \((1-x-y)\overrightarrow{A} + x\overrightarrow{B} + y\overrightarrow{C}\). But these are also the signed area ratios \(([PBC] : [PCA] : [PAB])\) as \([PCA], [PAB]\) have their bases along the \(y\) and \(x\) axes respectively (\([PCA] = \frac{1}{2}x, [PAB] = \frac{1}{2}y\) ), and since \([PBC] + [PCA] + [PAB] = [ABC]\), \([PBC] = \frac{1}{2}(1 - x - y)\). So, these definitions are equivalent.

Exercises (maybe don’t read below)

- Find the non-absolute barycentric coordinate expressions for the following points of triangle \(\triangle ABC\) (in terms of side length/angle expressions if necessary):

- Centroid \(G\)

- Incenter \(I\)

- \(A, B, C\)-Excenters \(I_a, I_b, I_c\)

- Orthocenter \(H\)

- Circumcenter \(O\)

… Answers

Personally, I’d use the area definition for all of these.

-

Centroid \(G = (1 : 1 : 1)\) \((\star)\) Incenter \(I = (a : b : c)\) \(A-\)Excenter \(I_a = (-a : b : c)\) Orthocenter \(H = (\tan A: \tan B : \tan C)\) Circumcenter \(O = (\sin 2A: \sin 2B : \sin 2C)\)

Problems

- (Mandelbrot 2013) Three concurrent cevians of \(\triangle ABC\), \(AX, BY, CZ\), intersect at \(P\). If \(PZ/PC = 2/3\) and \(PY/PB = 2/7\), find \(PX/PA\).

- In \(\triangle ABC\), \(BB_1\) and \(CC_1\) are medians. \(D\) is on \(BC\) such that \(L\), the intersection of \(AD\) and \(BB_1\), is the midpoint of \(BB_1\). \(K\) is the intersection of \(AD\) and \(CC_1\). What is \(C_1K/KC\)?

- The base \(ABCD\) of a pyramid \(FABCD\) is a parallelogram. The plane \(\alpha\) intersects \(AF, BF, CF,\) and \(DF\) at points \(A_1, B_1, C_1,\) and \(D_1\), respectively. Given that \(\frac{AA_1}{A_1F} = 2, \frac{BB_1}{B_1F} = 5, \frac{CC_1}{C_1F} = 10\), find the ratio \(\frac{DD_1}{D_1F}\).

- Prove the existence of the Gergonne point, the point of concurrency between the cevians to the points of tangency of the incircle. Find its non-absolute barycentric coordinates.

- Find the barycentric coordinates of the symmedian point.

- Let \(A_1\), \(B_1\), \(C_1\) be the feet of altitudes of acute triangle \(\triangle ABC\). Lengths \(A_1B_1 = 26, A_1C_1 = 28,\) \(B_1C_1 = 30\). Find the area of triangle \(\triangle ABC\).

Resources

- http://www.aquatutoring.org/TYMCM%20Mass%20Points.pdf

- https://www.journal-1.eu/2016-1/Francisco-Javier-Problems-pp.36-44.pdf

- https://web.evanchen.cc/handouts/bary/bary-full.pdf