Combinatorial Game Theory (and mini Minimax)

Solved Games.

A lot of games like tic-tac-toe, Connect 4, Shogi, and chess are (in the case of chess, unfortunately) described as solved.

Combinatorial games are two-player games in which players take turns, and there is perfect information, i.e. both players know the same information, which includes possible states after each move, and nothing is based on chance.

An added bonus for the three examples is that they are finite, in that there are a finite number of game states (and a finite number of ways to win), also meaning that the game cannot go in an infinite loop.

These end up satisfying all the conditions to be a “solved” game according to Zermelo’s Theorem, which states that in a finite combinatorial game, one of the two players has a strategy that can guarantee at least a draw (and if there is no possibility for a draw, then a player has a winning strategy).

We’ll get to the proof in a bit, but here are some introductory examples:

Nim

- Problem: Max and Julia have a pile of \(200\) cookies and on each move, they have the choice of taking \(1, 2, 3, ...\) or \(6\) cookies and removing them from the pile.

MaxJuliaMax goes first. The player who cannot make a move loses. Who wins with optimal play?

Our approach is to look for a winning strategy for starting values smaller than \(200\). Let’s look at the first few values to start on, \(1\) through \(7\), and we’ll label \(W\) as winning for Max, and \(L\) as losing for Max.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(L\) |

It’s clear that anything \(1\) through \(6\) is winning for the first player, Max, because he can remove everything from the pile. But, then for \(7\), we see that he cannot remove all, and any of the \(6\) possible moves will result in some number \(1\) throught \(6\) left, in which case Julia can remove the rest and win.

Note that if Max makes a move that lands on a position that was winning for him, then Julia can steal his strategy and win, so Max always wants to make a move that lands on a losing position. In the case of \(7\), it isn’t possible to have Julia play from a losing position, so it is losing for Max.

Let’s look at the next \(7\).

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(W\) | \(L\) |

Would you look at that. It’s the same thing. We get this again because from any value \(x\) that is \(8\) through \(13\), Max can remove \(x - 7\) to force Julia to play from losing position \(7\). Then, \(14\) must lead to a winning position so it is losing.

You can essentially induct up to \(200\) and realize that since \(200 \equiv 4 \mod 7\), it will be winning for Max.

Chocolate Bar

- Problem: A \(9 \times 5\) chocolate bar lies on the table. Max and Julia take turns breaking some non-single-square remaining portion the bar into two pieces along one of the grid lines. A player loses when only single squares remain. Max goes first. Who wins with optimal play?

This one’s a bit boring. On each move, it holds true that one piece is broken into two, or that the number of pieces increases by \(1\). Starting from \(1\) piece, we then know Max is always handed a state with an odd number of pieces. So, he is handed the final state of \(45\) individual squares, and Julia wins.

Invariants and things of the sort can show up a lot in combinatorial games. That and one player stealing the other player’s strategy.

- Problem: A \(9 \times 5\) chocolate bar lies on the table. Max and Julia take turns breaking a piece off the bar along the grid lines and eating it, until there is no chocolate left. The player to make the last move (eats the last square) loses. Max goes first. Who wins with optimal play?

This one is less boring. Notice that if both players play optimally, then the last player will have to take a \(1 \times 1\) square (unless they recognized that they were going to lose anyway… either way then at some further move they would have to play until there was a single square). So, it could be in Max’s interest to maintain a square chocolate bar.

This is indeed the strategy. On his first move, he can break \(9 \times 5\) into \(5 \times 5\), then on each of Julia’s moves, when she breaks along one grid line, she cannot form a square and she will break it into a bar \(a \times b, a \neq b\). Then, Max can break it into a square of side length \(\min(a, b)\). The side length strictly decreases between each of Max’s moves, so it either reaches \(0\) from Julia’s move (so she loses), or it reaches \(1\), so Julia has to take the single square. In any case, Max wins.

Double Nim

- Problem: Max and Julia have two piles of cookies, of size \(100\) and \(150\), and they take turns removing any number of cookies from any one of the piles. The player to make the last move loses. Max goes first. Who wins with optimal play?

Now it’s boring. This one nearly maps to the chocolate bar problem. We can say that the size of the first pile is the length of the bar, and the size of the second is the width. At any move, the player shortens one dimension by any amount by breaking off a piece. So, Max can nearly keep the piles even to guarantee a win. The only difference we have to cover is when one of the dimensions is \(0\).

This is winning when the other pile is size \(> 1\), because all but \(1\) can be removed to force the other player to lose. Max can follow the following rules to guarantee a win:

- If Julia cuts a pile down to \(0\), cut the other to \(1\).

- If Julia cuts a pile down to \(1\), cut the other to \(0\).

- Otherwise, make the piles of even size.

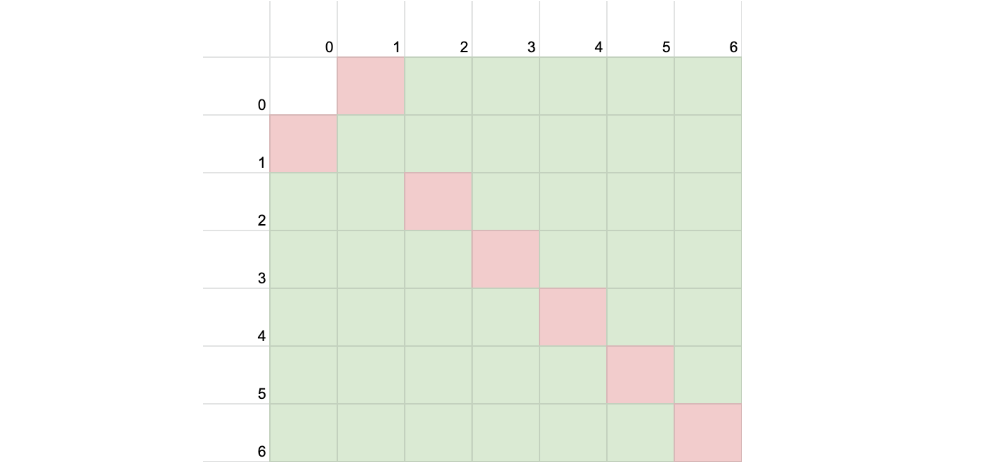

Note this chart:

Given any configuration, Max can force Julia to play from a losing configuration because from any winning square, there exists a square either to the left or above it that is losing, and is therefore one move away.1

Game Cost

Let us reframe our game, more generally, in terms of the “cost” of a position. For games like Nim, this may just be \(1\) or \(-1\) to represent whether a position is winning or losing.

More specifically, we can say that one player wants to maximize the cost of the game, and the other player wants to minimize the cost to win.

As an example,

- Problem: Max and Min (who is also Julia) have a fence of \(20\) boards in a row. They alternate moves, and on each move, they can paint one board of the fence either blue or red. At the end, they count the number of color changes (the number of pairs of one blue, one red board that are adjacent) and Min pays that amount of dollars to Max. Max starts. What is the minimum cost Min can guarantee? And maximal that Max can guarantee?

As a note, the cost may be at minimum \(0\) if Max and Min paint all the boards the same color. At maximum, it is \(19\) for alternating colors.

It turns out that they can both guarantee the same cost of \(9\) with the following strategies:

- Max: makes \(10\) moves. For any move after his first, he can guarantee that there is an unpainted board next to a painted board, in which case he can pick the opposite color of that board and guarantee at least one color change on each move, totaling \(9\).

- Min: can split the boards into pairs, associating boards \((1, 2), (3, 4), ..., (19, 20)\). On each move that Max makes, she can paint the other board within that pair with the same color. Then, at worst, there are \(10\) pairs alternating in color, totaling \(9\) color changes.

Let’s consider what the strategy then is for two players, Min and Max, trying to minimize and maximize the cost, respectively. We can define from the terminal (end of game) position the cost of a position according to this:

- If it is Max’s move, the cost of his current position is the maximum of the costs of the positions he can go to.

- For instance, if Max goes last in painting a board and he must paint one that is between two red boards, he will pick to paint it blue.

- Similarly, if it is Min’s move, the cost of her current position is the minimum.

If both players play optimally, this game will ultimately always end in the same way, with a final cost of \(9\).

Zermelo’s Theorem

Let’s look at the information we have about a general game as we’ve defined it: finite, combinatorial.

The game can be represented as a set of position vertices, \(V\), which we will write as the disjoint union:

\[V = P_T + P_{min} + P_{max}\]where \(P_T\) represents terminal positions, \(P_{min}\) represents vertices at which the min player makes a move, and \(P_{max}\) the max player’s move. Directed edges will represent moves that can be made from one position to another.

In a directed graph \(G\), vertex \(v \in P_T\) if and only if \(v\) has outdegree \(0\), i.e. cannot have a move made from it. \(P_{min}\) and \(P_{max}\) we will define as disjoint not necessarily in that only one player can have a move from a certain game state (ex. in Nim of \(200\) cookies, Max or Julia may play from \(198\) if the first moves are \(2\), or \(1\) and \(1\)), but that the game state is a certain way, and it is a certain player’s turn. And, there must exist no cycles in the graph.

We will also say that each \(v \in P_T\) has a cost that the min player pays to the max player (so Min wants to minimize, and Max wants to maximize).

Zermelo’s Theorem states that there exists a cost \(c_0\) and a strategy for each player for which Min can guarantee a cost \(\leq c_0\), and Max can guarantee a cost \(\geq c_0\) (so the cost of the game with optimal play is \(c_0\)).

Proof: We essentially do what we were doing before, and propagate the cost function \(c(v)\) (which currently exists for \(v \in P_T\)) to all other vertices according to the following rules:

- For \(v \in P_{max}\) with \(S_v := \{ u \in V \vert (v, u) \in E(G) \}\) \(= \{ u_1, u_2, ..., u_n\},\) \(c(v) = \max(c(u_1), c(u_2), ..., c(u_n))\).

- For \(v \in P_{min}\) with \(S_v\) defined similarly and written as \(\{ u_1, u_2, ..., u_n\}, c(v) = \min(c(u_1), c(u_2), ..., c(u_n))\).

- For Max, we are taking the maximum of the costs of the possible next positions and saying that is equivalent to the cost of the current position. Similarly for Min.

We claim this is possible to evaluate for any vertex, by our assumptions of finiteness and no cycles. Given a certain vertex \(v\) that we want to find the cost of, we must first evaluate the costs of all \(u \in S_v\). So, starting at \(u_1,\) then \(u_2,\) etc., we can do so. We’ll say the same for any \(u_i,\) and evaluate all the nodes it leads to first. Each time we do so, we cannot repeat a vertex that is already in the process of being evaluated, otherwise there exists a cycle. And given finiteness, we must reach a vertex that will only lead to terminal positions and/or already evaluated vertices.

This will lead up to our starting position vertex, on which we can guarantee the cost \(c_0\). There will exist some path along edges for which each next vertex has cost \(c_0\). Both players ultimately follow the strategy of picking a next vertex with cost \(c_0\), because if Max were to make a different move, it would have to have a lower cost, which would then imply that Min can guarantee \(\leq\) that chosen cost. Similarly for Min, any move besides one leading to a vertex \(v\) with \(c(v) = c_0\) would have to lead to a higher cost that Max can guarantee.

Minimax: Tic-Tac-Toe

The minimax algorithm for combinatorial game AIs essentially does just that. A minimax() function can be used to recursively evaluate the cost of each vertex, then pick the best move according to cost.

I (Julia) made a tictactoe minimax in p5 to demonstrate. You are player 2, and the AI is guaranteed at least a tie against you. Here’s the code.

Games!

- Max and Julia have a sheet of paper with a coordinate plane and an axial rectangle with opposite corners at \((1, 1)\) and \((m, n)\). On each move, they choose to cross out a point within the rectangle that is not already crossed out \((x, y)\), as well as all points within the rectangle \((x_0, y_0)\) with \(x_0 \geq x\) and \(y_0 \geq y\). Max starts, and the player who makes the last move loses. Who wins with optimal play?

- (Nim-ish but Julia got mad she was losing) Max and Julia have two piles of cookies of size \(100\) and \(150\), and on each move, a player can remove any number of cookies from one pile as long as the two piles do not become equal in size if both are nonempty. Max goes first, and the player to make the last move wins. Who wins with optimal play?

- Given a pair of positive integers \((a, b)\), Julia and Max alternate moves and on each move, they subtract a multiple of the smaller one from the larger one, so long as both remain positive. Max starts, and the player who cannot make a move loses. Who wins with optimal play?

- (Mathcamp 2022 Qualifying Quiz) Julia and Max are playing a solitaire game with marbles. There are \(n\) bowls (for some positive integer \(n\)), and initially each bowl contains one marble. Each turn, each player may either remove a marble from a bowl, or choose a bowl \(A\) with at least one marble and a different bowl \(B\) with at least as many marbles as bowl \(A\), and move one marble from bowl \(A\) to bowl \(B\). Max starts, and the player who cannot make a move loses. Prove that among any three consecutive values of \(n\), there is at least one value for which Julia has a winning strategy.

-

This ratio is sad but I normally have a better win ratio against Max in skill based games. :) ↩