Turing Completeness and Turing Machines

Turing completeness and turing machines serve as models for computational systems’ behavior and structure. This article contains a brief history and description of the two.

Entscheidungsproblem

As for some context, a formal language is a set with certain elements (letters of an alphabet) and rules specific to the element that can be used to create well-formed statements (it’s a bit like the English language I guess…). In terms of math, it is equivalent to there existing defined symbols and a set of axioms that all else can be deduced from.

Consider this: Is mathematics a formal language?

This is a problem of contention because one definition/axiom can lead to conflicting conclusions within different fields. For instance, the set-theoretic definition of natural numbers \(\mathbb{N} = \{ 0, 1, 2, ...\}\) differs from the typical one, \(\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, ...\}\). However, individual fields like Euclidean geometry are built on a few postulates and axioms that can be used to build all else.

A problem proposed by David Hilbert in 1928 asked whether there exists an algorithm for a general set of letters and axioms that can determine whether a statement is universally valid, meaning it satisfies the conditions of all axioms. This problem was named Entscheidungsproblem or the decision problem, and it is still debated.

Turing’s Approach + Turing Machines

Turing answered this problem negatively, saying no general method for arbitrary rules and letters exists, but it relies on the idea that all computation is possible through the Turing machine model.

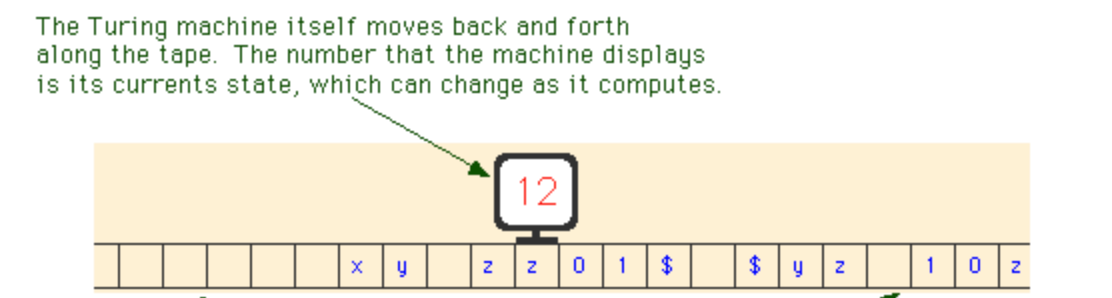

Turing Machine Model, via Hobart and William Smith Colleges

This machine model operates as inputting an infinite tape of characters, and as having a current state. At each spot on the tape, it will read the character, then may change its state according to its previous state and the character and/or change the character, then move on to the next one or halt. In the image, the machine has current state 12 when moving to the z, and according to that state and character, it may change to state 1 and the character to @, because that was the condition for z, 12. It may also stop given this condition.

Turing concluded that there does not exist such a machine that can determine whether any other arbitrary machine will print a certain character, or is “circular” (i.e. the next character can be computed in a finite number of steps). These statements are also relevant to the halting problem, which he likewise proved to be indeterminable.

One way to think about this is essentially like prediction. An arbitrary Turing machine has a certain fixed final state and printed character for a given starting state and character it just read. Let’s say the solving machine determined the result to print/not print/stop at a certain character. The arbitrary machine could have a change of input that would result in something contradictory before each instance of such a condition being true, and the solving machine would have no way of knowing such input.

This essentially generalizes to solve Entscheidungsproblem, because such uncertainty may exist in answering an input to an arbitrary formal language.

It was only a few years after this problem that the Turing machine was born, and it is considered the basis of any mechanical computation machine.

But Turing Machines are… so Simple

Turing machines work for any computation, but their structure says essentially nothing about efficiency and practicality.

There are currently three main computational models, one being the Turing machine, and the others the random-access machine and the counter-machine. Random-access memory can improve efficiency by allowing data modifications that have near the same time complexity irrespective of position.

Quantum computing also disregards all of this use of binary by relying on the transmission of qubits, which are subatomic particles that can communicate much more information in a single particle via their quantum properties.

Turing Completeness and Cool Examples

By definition, Turing completeness is the property of being able to simulate a Turing machine (essentially any computational machine).

In terms of constructing a machine (using binary input), this comes down to being able to respond to conditional statements. If a certain input condition is true (1) given the current condition, do one thing and produce some output, otherwise (0), do another thing and produce some other output. This can create all of your and, or, xor, else if, etc. statements.

Here are some cool examples of Turing complete scenarios:

-

(undeniably best) Conway’s Game of Life, Life in life (with terrifying music), Julia’s article

-

Minesweeper, Infinite versions of minesweeper are Turing complete

-

Physics. Code Bullet Marble Calculator

-

Minecraft redstone, Conway’s Game of Life in Minecraft

-

Ethereum/blockchain system, Turing Completeness and Cryptocurrency

Sources

- https://media.consensys.net/ethereum-isnt-turing-complete-and-it-doesn-t-matter-anyway-625061294d3c

- https://www.gwern.net/Turing-complete

- https://freemanlaw.com/turing-completeness-and-cryptocurrency/

- https://www.cs.odu.edu/~zeil/cs390/latest/Public/turing-complete/index.html

- https://www.gwern.net/docs/www/web.mat.bham.ac.uk/ df628d6d591be7690ceedcbaffa0500eadff3e2f.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i1e0T7lAELQ

- https://youtu.be/xP5-iIeKXE8

- https://youtu.be/jaoSzCfa9OM